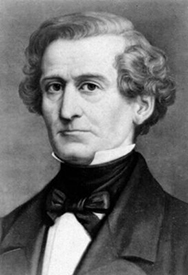

SYMPHONIE FANTASTIQUE

Épisode de la vie d’un artiste. Op. 14 (1830)

Born: 11 December 1803, La Côte-Saint-André, France

Died: 1869, Rue de Calais, Paris, France

The story of the symphony is a self-portrait of its composer, Hector Berlioz.

Hector Berlioz was born in 1803 in La Cote St André, a small town near the French Alps. His mother was a devout Catholic and his father a noted doctor. At twelve, Berlioz discovered music. He became an accomplished flautist, picked up the guitar and then taught himself to play drums.

As a teen, Berlioz suffered from isolation and bouts of uncontrollable mood swings. These dramas, coupled with his fantasies of love and loss, provided Berlioz with the raw materials for his life’s work.

Berlioz left home for Paris to study medicine, but soon turned his attention to music. His father allowed him time to prove himself in this new endeavour but his mother considered theatrical ambitions sinful and disowned him.

Symphonie Fantastique was among only several works that Berlioz preserved from his tumult of creativity during 1824 through 1830. A voracious reader, Berlioz discovered the latest works at the forefront of progressive and romantic thought in Paris: Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (trans. By Gérard de Nerval, 1828), Contes Fantastiques (Fantastic Tales) by E. T. A. Hoffmann (Paris, 1829), Confessions d’un anglais mangeur d’opium (Confessions of an English user of opium) by Thomas de Quincey (trans. By Alfred de Musset, 1829) amongst others. These and the plays of Shakespeare ignited Berlioz’s highly susceptible imagination and influenced his choice of subjects and narratives.Symphonie fantastique, in its original scoring, is an epic for a huge orchestra. Through its movements, it tells the story of an artist’s self-destructive passion for a beautiful woman. The symphony describes his obsession and dreams, tantrums and moments of tenderness, and visions of suicide and murder, ecstasy and despair.

Movement I: Rêveries-Passions (Reveries-Passions)

In 1828, Paris buzzed with two sensations, Beethoven and Shakespeare. Beethoven’s music established the Romantic ideal; instead of fitting suitable music into classical forms, Beethoven reconfigured the symphony and the personnel of the orchestra to accommodate his emotional expression. Berlioz couldn’t get enough of it.

Shakespeare, as presented by the Irish actress, Harriet Smithson, changed Berlioz’s life forever. From the moment he saw her, he was obsessed. Symphonie fantastique is nothing less than Berlioz’s extravagant attempt to attract Harriet’s attention.

The piece begins by introducing the listener to the vulnerable side of the protagonist, the Artist.

The object of the Artist’s love is represented by an elusive theme called the “idée fixe” – the object of fixation. It appears four times in this movement. Violins and flute float flirtatiously through the charming melody. The noise of the rest of the orchestra represents the Artist’s frustration and despair. Frightening outbursts alternate with moments of the greatest tenderness. It all leads to a moment of complete frenzy and collapse. Symphonie fantastique premiered in Paris in 1830. Reactions were mixed. Most disappointingly, Harriet Smithson did not attend.

Movement II: Un bal (A Ball)

The second movement invites us to a ball. The harp leads the waltz as the music alternates between watching the dancers and spying on the Artist trying to gain the attention of his beloved. After the disappointment of the premiere, Berlioz decided to compete for the prestigious Prix de Rome. For the competition, entrants were given a melody and had to write a fugue (a form with very strict rules) on the spot. It took Berlioz four years to master the devilish form but at last he won. The Prix de Rome earned Berlioz the national recognition he craved plus a subsidy to study for two years in Rome.

Movement III: Scène aux champs (Scene in the Country)

While in Italy, Berlioz explored the musical landscape of the countryside and continued to polish Symphonie fantastique.

The Third Movement of Symphonie fantastique opens with an echo from Berlioz’s childhood: the sound of a cowherd’s melody. Berlioz uses the orchestra to create the sense of suspension of time that intimacy can bring. It borrows structural and melodic ideas from the pastoral movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6.

This movement was the most difficult to compose for Berlioz. The music is always only a heartbeat away from the jealous rages that arise when the Artist sees his beloved with someone else.

By 1832, Berlioz was back in Paris and determined to win public opinion with a new version of Symphonie fantastique. He arranged for a second premiere. Meanwhile, Harriet Smithson was no longer a favourite in Paris and was deeply in debt. Berlioz sent her tickets to the best seats in the house for opening night.

Movement IV: Marche au supplice (March to the Scaffold)

In the fourth movement Berlioz begins to reveal the truly sinister side of his imagination.

The program notes read, “The Artist, knowing beyond all doubt that his love is not returned, poisons himself with opium. The narcotic plunges him into sleep, accompanied by the most horrible visions.”

The first of those visions is the “March to the Scaffold.” In it, the Artist is executed for the murder of his beloved. The march echoes the sound of the real life bands that would accompany the condemned to their execution. The military band escorts the prisoner to the enthusiastic cheers of the strings. In the last instant of his life the Artist thinks of his beloved. Her theme begins but is truncated by the blade of the guillotine. The Artist’s head bounces down the steps, the drums roll and the crowd roars.

Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863). Witches’ Sabbath (1831-32)

Movement V: Songe d’une nuit du sabbat (Dream of a Night at a Witches’ Sabbath)

The fifth movement is a satanic dream. The Artist sees himself in the midst of a ghastly crowd of sorcerers and monsters assembled for his funeral. The air is filled with strange groans, bursts of laughter, shouts and echoes. Suddenly, the Artist’s beloved appears as a witch, her theme distorted into spiteful parody.

A vast church bell begins to chime the peal of death. Bassoons and tubas bark out the Dies Irae – the traditional funeral chant. The orchestra divides into teams to enact a sinister ritual.

The groaning theme from the beginning of the movement transforms into a merry black Sabbath dance. The form of the dance is the fugue – after struggling to master the form for the Prix de Rome, Berlioz chose the fugue to represent his vision of hell.

The music whips into a frenzy as it bears the soul of the Artist to his damnation. His beloved gloats over the scene. Such an ending to a symphony had never been previously heard.

At the conclusion of this second premiere, the audience erupted in applause. Harriet Smithson finally understood that Symphonie fantastique was about her.

Hector and Harriet started to act out in reality what the Symphonie fantastique only imagined. He began to court her in earnest and, in doing so, did something desperate indeed. From his pocket, Berlioz produced a vial containing a lethal dose of opium. Before Smithson’s eyes, he swallowed it. She became hysterical and agreed to marry him. Then, conveniently, he produced the antidote from another pocket and swallowed that. After recuperating, Hector Berlioz and Harriet Smithson were married in 1833. Ultimately, Smithson and Berlioz separated, but he always took care of her. Harriet died in 1854. They are buried together in Montmartre Cemetery.

Berlioz – A Somewhat Complicated Love Life!

For all the concentration on the “Idée fixe” thematic motive in the Symphonie Fantastique, there are actually three women represented in the symphony:

1. Estelle – both the name of a childhood girl who spurned Berlioz’s advances at the age of six (she was twelve) as well as the Estelle of the poem ‘Estelle et Némorin’ a pastoral play by Jean-Pierre Claris de Florian (1755-94) which the young Berlioz found in his father’s library. Interestingly, the real Estelle and Berlioz in fact became gentle friends as widow and widower in the final chapter of Berlioz’s life.

2. Harriet Smithson is the acknowledged cause célèbre. Harriet’s initial rejection of Berlioz influenced the later sections of the symphony during which the artist-hero-lover dreams he has killed his beloved. She, an image of Harriet, morphs into a horrible witch and joins in an orgiastic dance and he dies by guillotine!

3. The last female influence was Camille Moke. Having been rejected by Harriet, Berlioz fell in love with Camille during the months he was completing the symphony. A piano teacher at the girls’ school where he taught guitar. Camille likely spread malicious gossip surrounding Harriet with her manager, helping Berlioz steer away from his fixation on Harriet. Following the first performance of Symphonie Fantastique on December 5, 1830, Camille and Berlioz became engaged. But she left him for a wealthy businessman, soon becoming Camille Pleyel, part of the prominent Parisian family that manufactured pianos.