Arnold E. T. Bax

Arnold E. T. Bax

Mediterranean for orchestra

Originally scored for piano, Mediterranean is a waltz in 3/8 time, having been composed after a trip Bax took to Majorca with his brother and fellow composer Gustav Holst. As an accomplished pianist, Bax knew the technical and timbral possibilities of the instrument intimately. He was quite adept at creating an atmosphere for these short programmatic “character” pieces.

This work, which Bax ultimately arranged for orchestra, has a decidedly Spanish flair (similar to Ravel’s Alborada del gracioso, which also started life as a piano piece) and light-hearted wit.

Edward Elgar

Edward Elgar

King Arthur Suite

Edward Elgar (1857-1934) first became friendly with Lawrence Binyon, the celebrated British First World War poet, through his setting of three of Binyon’s poems as The Spirit of England, Elgar’s last cantata first performed in 1917. When, towards the end of 1922 Binyon was commissioned by London’s Old Vic theatre to write a play on the life of King Arthur, he turned to Elgar to provide incidental music for the play.

Elgar completed a score of some 90 pages. Restricted by the orchestral forces at his disposal: flute (doubling piccolo), clarinet, 2 cornets, trombone, drums, percussion, harp, strings and piano, he scored eight of the nine dramatic scenes. Six of them are heard in this suite:

I. King Arthur and Sir Lancelot

II. Elaine

III. Banqueting Hall at Westminster

IV. The Queen’s Tower at Night

V. Battle Scene

VI. Arthur’s Journey to Avalon

Ignoring the ‘incidental music’ tag – the label is inappropriate – the score contains some of Elgar’s most powerful and convincing post-1920 music. Michael Kennedy in his book, ‘A Portrait of Elgar’, describes it as “a superb score”. Elgar reworked the third scene, ‘Banqueting Hall at Westminster’ to form the basis of the second movement of his uncompleted third symphony later completed by Anthony Payne.

Arnold E. T. Bax

Arnold E. T. Bax

From Dusk ‘Till Dawn (Ballet)

1. Prelude: Summer Night at the Window

2. The Wind Dances in the Garden

3. Midnight Strikes

4. The Awakening

5. The Flower’s Dance

6. The Dancer and the Clown

7. The Wind Dances through the Room

8. The Clock Strikes One

9. The Flowers Dance Again

10. The Clock Strikes Two

11. The Dancer falls weeping into the Clown’s arms

12. The Clown thrusts her aside and scolds her

13. They quarrel

14. The Wind

15. The Dancer humbly draws the Clown’s attention to the sad fate of his rival

16. The Dancer turns back to the Clown

17. Dawn

18. Everything is still, a sad silence reigns

19. The Wind blows the Dancer into the Clown’s stiff arms

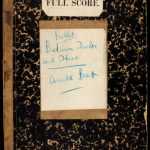

Originally titled ‘Between Twelve and Three’ (1917) this performance includes all the music from Bax’s Ballet Ruses inspired work for his ballet in one act. The ballet was produced in December 1917 with the enthusiastic balletomane, Mrs. Christopher Lowther (who also commissioned the work) – later to become Lady Cholmondley – in the lead.

Some of this score was given in a concert performance by the young Adrian Boult in 1918. It then disappeared until revived in a concert at the 1982 Petworth Festival, UK. This is the first time the score has been played anywhere since then.

THE STORY OF THE BALLET

The story of the ballet is based around some china figures who lose their immobility one summer night.

The curtain rises to reveal the summer night seen through a garden window. The wind dances in the garden as moonlight gradually illuminates the room. At the stroke of midnight various ornaments stir – a Dresden figure, a clown and a Russian ballerina.

The flowers gradually awake one by one and dance. The dancer and the clown embrace and dance together.

The clock strikes one.

The flowers dance again, and the Dresden figure passes below where the clown and dancer are sitting. The Dresden figure makes amorous moves toward the dancer, and they engage in a flirtatious dance (the letter part ‘The Flowers Dance Again’) which gets even faster, the Dresden figure becoming more and more excited, finally kissing her fervently. The dancer boxes his ears.

The clock strikes two.

The dancer falls weeping into the clown’s arms, but he thrusts her aside and scolds her. As they quarrel, the Dresden figure eggs on the clown. The wind enters the room violently and boisterously (with wind machine in the orchestra) and at a climax the Dresden figure is blown over with a crash. Chastened by this run of fortune, the dancer tries to involve the clown but he makes an angry gesture of rejection. She tiptoes to the Dresden figure but finds him too broken to speak. She turns back to the clown but he again rejects her.

Dawn: the clock steps forward and all return to their stands as it strikes three.

Everything is still and a sad silence reigns. In a final burst of high spirits the wind thrusts his head through the window and with a great puff blows the dancer into the clown’s stiff arms. The wind dances wildly and points mischievously at the couple (to a familiar phrase from Mendelssohn’s Wedding March on the flute) as the curtain falls.

Frank Bridge

Frank Bridge

Lament (for Catherine, aged 9 “Lusitania” 1915)

On May 7, 1915, a German U-Boat fired torpedoes at the RMS Lusitania, a civilian ocean liner, and sank it in the Atlantic. 1,195 people died, the incident rousing international condemnation as non-naval vessels were presumed to be non-combative and not to be engaged. It is generally accepted that the sinking of the Lusitania was a catalyst for America entering the War several years later. Among the lost was Catherine, a 9-year-old girl who died with her family. The loss impelled Bridge to compose an elegy, creating what is, possibly, the most beautiful piece of music ever written about a humanitarian nautical disaster.

By any standard, the sinking of the Lusitania was a war crime perpetrated by the German navy on civilian passengers, including citizens of neutral countries. The reaction in both Great Britain and America was unbridled indignation that spilled over into sporadic rioting and looting that targeted businesses whose owners had German, or merely German-sounding, names.

The American press, mostly pro British, was uninhibited in its desire to condemn both the Kaiser and his minions while wrenching the hearts of its readers. About a week after the Lusitania sank, the New York Times published a prominently displayed photograph (taken by the distinguished photographer Mathilde Weil) of Gladys Crompton holding her youngest child, a mere babe in arms, surrounded by an aureole provided by the rest of her angelic-looking children. This photograph was reprinted widely in newspapers around the globe. While other families perished on the Lusitania, this photograph, cunningly posed by Weil to recall Renaissance paintings of the Madonna and Child with attendant saints, turned the Crompton family into a symbol of innocence that had been snuffed out by German barbarity. German and Austro-Hungarian newspapers only exacerbated the public relations disaster for their respective nations by printing jingoistic articles about the invincibility of German submarines.

Indeed, such an attack on civilians and citizens of neutral countries at sea was virtually unheard of in modern European war fare before the ‘total war’ tactics adopted by all sides during the First World War. (Astoundingly, despite the clear danger posed by German submarines, the British navy had declined to provide an escort for the Lusitania.)

On Monday 14 June, 1915, Frank Bridge composed a six-minute piece for string orchestra. In addition Bridge placed on the music this inscription:

Catherine

Aged 9

‘Lusitania’ 1915

By explicitly identifying Catherine as the source of his inspiration, Bridge created a sui generis a tradition for commemorating a new category of wartime casualty (Bridge’s Lament preceded Debussy’s bitter condemnation of German atrocities against Belgian children, Noël des enfants qui n’ont plus de maison, by several months).

Bridge sustains a mood of tender lamentation through his imaginative use of rhythm and pitch materials. The swaying compound metre evokes both a lullaby and the lapping of waves. The dynamic range is quiet throughout, rising only once from piano or pianissimo to a mezzo-forte that dissipates rapidly. The melodic contour is pentatonic, like a child’s nursery rhyme, but the tonality is unstable bound with a complex harmonic idiom built on the use of whole-tone hexachords.

Catherine’s family perished alongside her. The remains of her three brothers (the only bodies recovered) were interred in Ireland.

Arnold E. T. Bax

Tintagel

The ruins of Tintagel Castle stand today on the rugged and wind-swept northern coast of Cornwall. Though little is known for certain of the history of the castle, Tintagel is most famous for its associations with the legendary King Arthur.

The Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth, writing in the 12th-Century, tells of the palace belonging to Gorlois, Duke of Cornwall, whose wife, Ygerna, had aroused the passions of King Uther Pendragon. In the ensuing dispute, Uther laid siege to the castle. In the voice of one of Uther’s soldiers, Geoffrey states that, “The castle is built high above the sea, which surrounds it on all sides, and there is no other way in except that offered by a narrow isthmus of rock.” Unable to breach the walls, Uther enlisted the assistance of the magician Merlin, who cast a spell making Uther appear as Gorlois. Thus, Uther slipped into the castle unopposed and was able to seduce Ygerna. The son born of this night was to become the young King Arthur.

Shortly after Geoffrey, Chrétien de Troyes, a poet of northern France from approximately 1160 to 1180, also wrote of Tintagel as an important location in Arthur’s life. According to Chrétien, Tintagel was one of the castles at which Arthur held court.

In the fifteenth century, Sir Thomas Malory retold the tale of Arthur, expanding greatly on the collected writings of past authors, and again naming Tintagel as the king’s birthplace and reasserting the importance of the site. It is Malory’s telling of the tales of Arthur and his knights that is most commonly known to enthusiasts of the legends. More can be found involving Tintagel in the works of Malory than merely its status as the place of conception of the future King Arthur.

In The Book of Sir Tristram de Lyones, the first story is called “Isode the Fair.” This tale establishes Tristram as the nephew to King Marke, Lord of Cornwall and royal resident of Tintagel Castle. Tristram comes to defend his uncle’s kingdom from attack by Sir Marhalte of Ireland, and the two noblemen battle in single combat, during which Tristram is poisoned, but fights on to victory. In gratitude, the young princess Isode nurses the knight back to health, and the two fall in love. King Marke thinks Tristram to be the greatest knight he has known, and Isode is commonly thought of as “the fairest lady and maydyn of the worlde.”

In the mid-19th century, Alfred Tennyson, the English Poet Laureate regarded by many as the chief representative of the Victorian Age of poetry, took up the subject of Arthur, using Malory as his main source material. He dealt with the subject first in the narrative poem the “Lady of Shalott” of 1832, and then in the later poems “Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere” and the “Morte d’Arthur” of 1842. His comprehensive narrative, Idylls of the King, comes from 1869, only four years after Richard Wagner’s music drama, Tristan und Isolde.

HOW TINTAGEL IS PUT TOGETHER MUSICALLY

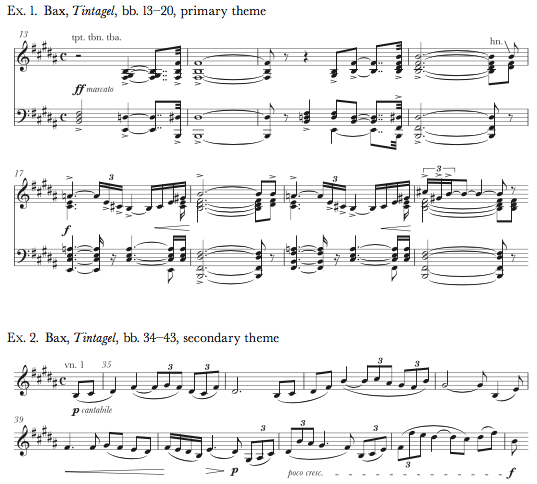

The work as a whole is comprised of three sections. The first of these sections is majestic and grandiose, proclaiming two main themes, each with a number of subsidiary ideas, which will return in the gloriously varied closing section. Between these comes a rhapsodic middle section of highly elemental feeling.

In the opening bars of Tintagel. Shimmering strings undulate as the woodwinds trill, creating the sense of breakers striking incessantly against the rocks below the castle, while the harp provides flecks of sunlight glint off the swelling waves. One can even hear a gull, as portrayed by a single flute, circling and diving in the breeze. A majestic phrase in the brass, growing out of smaller motives, wells quickly to generate a powerful climax. The horns launch a gloriously nautical first main subject, a melody built from the component parts of the introductory motives. The entire process of moving from the opening bars to the first theme proceeds organically.

The main subject emerges in the flutes and violins with a marking of “cantabile” after 33 bars of what has been called “the most vivid sea music ever written.”

The second theme of this opening section is comprised of material similar to that of the first theme, but it is used in a much different way. Starting very quietly, the melody has a kind of lilt to it that is folk-like in nature. This theme, one of the more expansive orchestral themes in Bax’s repertoire, is surely the “love theme” of this work. We find the theme first in the violins and flutes, distinctive with its triplets and wide melodic leaps. From first hearing through the rest of the piece, the theme or elements derived directly from it can be found again and again.

A distinct change is felt in the middle section. The under-rhythm begins to loom larger, the wind rises, and a storm sweeps through the orchestra. “The Atlantic, a sinister personality, lifts up its head like Poseidon, and stares hostilely at the impregnable rock whereon the castle stands.” It is also in this middle section, though, that the magical moment of Tristan’s arrival occurs. His music is intermixed with the music of the storm throughout the section, and the ocean theme lets loose to bring the music crashing into the final section.

Over rocking woodwinds, the brass intone the welling phrase of the opening theme. Urgency builds, as the first subject is re-examined, this time over huge Atlantic rollers rather than playful waves. The second subject emerges from those invigorating waves, resplendent in a resounding climax filled with blazing horns followed once again by the first subject, equally brilliant in its trumpeted glory. Finally, the high energy of the moment abates, and the brass gives us a few final chords, pressing upward in a final few gusts against the shoreline.