The Great 20th Century Impressionists

RAVEL & RESPIGHI

M. Ravel Ma Mère L’Oye

arr. Iain Farrington for Chamber Orchestra

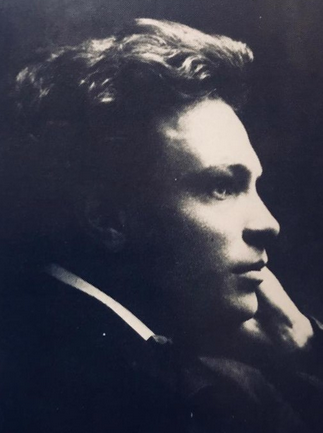

Maurice Ravel

Maurice Ravel (1875 – 1937)

Ma M’ère L’Oye was composed by Maurice Ravel for two young children, Mimi and Jean Godebski in 1908 as a four-hand work for piano. The piece was composed at the same time as his great piano masterpiece, the fiendishly difficult Gaspard de la nuit.

The work is in 5 short sections:

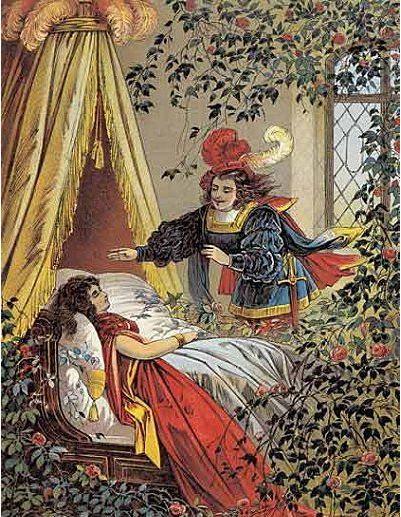

I. Pavane de la belle au bois dormant (Pavane of the Sleeping Beauty)

II. Petit poucet (Tom Thumb)

III. Laideronnette, impératrice des pagodes (The Plain Little Girl, the Empress of the Pagodas)

IV. Les entretiens de la belle et de la bête (The Conversations of the Beauty and the Beast)

V. Le Jardin Féerique

The opening section is only 20 bars long and serves as an introduction to the fairytales that follow transporting the listener into a world of pure fantasy and make-believe. A ‘pavane’ is a slow processional dance common in Europe during the 16th Century.

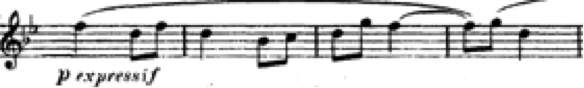

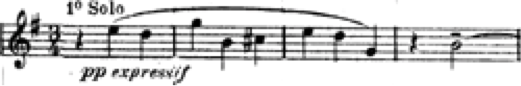

With a sleep inducing atmospheric opening, the “Pavane” begins with a theme shared by the flutes over the 20 bars of the opening section. This melody is lightly accompanied by a muted French Horn, pizzicati strings with counter-melodies in the Cor Anglais and French Horn.

A 2nd motive begins on clarinets over a descending counter-melody in the Cor Anglais, doubled by strings pizzicati.

The second movement is about the tiny character of Tom Thumb Tom, and his brothers, are abandoned in a forest by his parents who are so poor that they are unable to feed them at home anymore.

Tom leaves a trail of pebbles and the boys find their way home. As the family gets poorer, the boys are abandoned for a second time in the forest. This time Tom leaves a trail of breadcrumbs to help find their way home. But, unbeknownst to the boys and Tom, they discover the birds have eaten the trail of crumbs they have left.

Lost in the woods the boys are taken in by the wife of an ogre who; on his return home, vows to eat them. Tom outwits the ogre, tricks him out of all his valuable possessions and returns with his brothers back home.

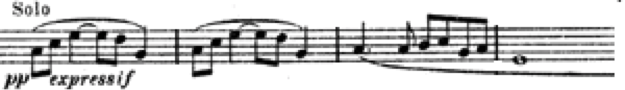

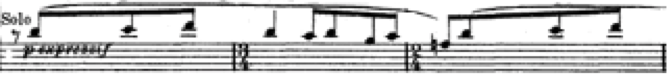

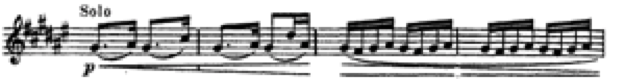

“He thought that he would easily find his way back with the help of the bread he had sown all along as he passed: but to his surprise he could not find a single crumb: birds had come to eat them up all.” (Cb. Perrault) The “petit poucet” is established by a 1st theme for Oboe solo, accompanied by scales passages in the violins harmonized in thirds.

A 2nd motive is performed by the Cor Anglais from the 12th bar on the Bb pentatonic (making use of only 5 notes) scale.

We return now to the 1st theme on the first Bassoon accompanied by strings playing glissandi imitating “bird singing”.

A last motive, based on the interval of a descending perfect 5th., is placed above a chromatic ostinato in the violas.

The Pagodas of the title of the 3rd. movement are not temples, but little porcelain figures with grotesque faces and nodding heads who, magically play to their Empress on instruments made from nutshells as she takes her bath. Ravel transports us to the mysterious East with its pentatonic scales and Balinese gamelan-orchestra effects. The composer was fortunate to have been present at the first great Exposition Universalle held in Paris in 1889 where, like Debussy, he was overwhelmed by the exoticism from Java.

In the story that inspired Ravel, Laideronnette is a Chinese princess who has been cursed with horrible ugliness and wanders for years, her only companion an equally ugly green serpent. Eventually they are shipwrecked on the island of the pagodas; little porcelain people, who take her as their queen. In the end, she marries the serpent (a handsome prince in disguise!) Both get magical makeovers and return to their former good-looking selves.

“She undressed and got into the bath. All of a sudden the little porcelain girls and boys started to sing and play instruments: some had theorbos made of nutshell, some viols made of shell of almonds: because the instruments had to be accommodated to their size.” (Mme. D’Aulnoy)

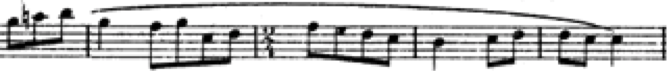

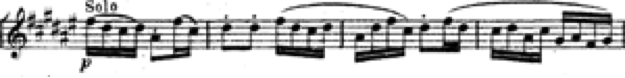

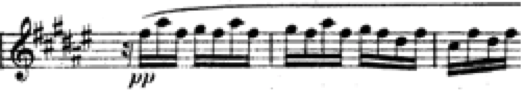

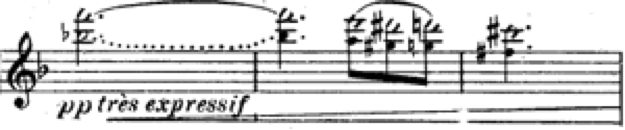

This movement is the heart of the piece because of its dimension and orchestral structure. Using a faux oriental-style melody, a fast and light theme is played by the piccolo on a pentatonic scale.

A 2nd motive, given in alternation between the Oboe and the Cor Anglais, is built on a syncopated rhythm of the strings,

alternating with a dotted rhythm motive in the 2nd Flute in the middle register, built on descending cells of 4 eighth-notes in the 2nd Bassoon, violas and celli.

Coming directly from the 1st theme, a sixteenth note motive doubled in octaves enters between the flutes, the Celeste then the Harp, accompanied by violin pizzicati in regular eighth-notes.

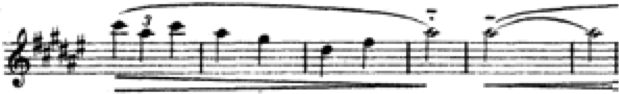

But this mood dissipates with a 2nd motive imitating the 1st theme in augmentation in the wind instruments dominated by the French Horn

and a subsidiary motive idea for solo Flute harmonized beneath in the strings.

The return of the Clarinet and French horns over which is superimposed the 1st theme in octaves on the Celeste with pianissimo punctuations in the Timpani along with shimmering Violin and Viola tremolandi is testament to Ravel’s genius as an orchestrator.

The Coda of this piece is built on the return of the 2nd motive starting in the Oboe over which a texture of continuous sixteenth-notes across the whole orchestra builds.

This movement has four narrative sections:

- Music that describes Beauty (followed by a short silence).

- Music that describes the Beast.

- A longer section that describes Beauty declaring her love – during which the music of Beauty and the Beast combine.

- The Beast changes into a handsome prince.

Beauty: “When I think of how good-hearted you are you do not appear so ugly to me.”

Beast: “Oh, Lady, yes, I do have a good heart but I am a monster.

Beauty: “There are quite a lot of people who are more of a monster than you.”

Beast: “If I were witty enough I would pay compliments to you but I am only a beast.”

…………………

“Beauty, will you marry me?”

Beauty: “No, my Beast.”

…………………

Beast: “I happily die because I had the pleasure to meet you once more.”

Beauty: No, my dear Beast, you shall not die: you shall not die: you shall live to become my husband!”

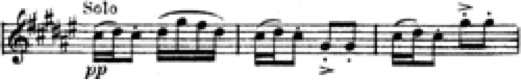

The “entretiens” come after a moderated waltz in which the melody played softly in the 1st Clarinet, then accompanied in the Harp doubled by the flutes, and later on in the 1st and 2nd violins.

But the frightening theme of the Beast stops this waltz with a descending chromatic figure in the low contrabassoon, alternating with the Beauty’s motive in F# played by the Flute and Oboe.

Becoming increasingly more animated, the waltz is interrupted by a 1 bar rest, a type of musical magic trick in with a harp glissando ends the enchantment of the Beast and reveals the charming prince illustrated by an eighth-note triplet in the orchestra with overtone glissandos in the 1st violins.

The Beast disappeared and all she saw in front of her was a prince more beautiful than Love who thanked her for having put an end to his enchantment. (Mme. Leprince de Beaumont)

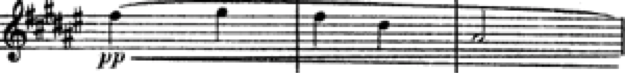

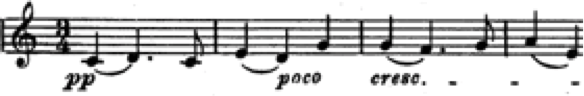

The final movement is the only one not specifically drawn from a fairy tale. The music conjures the slow procession of Sleeping Beauty’s awakening by Prince Charming. The Celeste is assigned the role of depicting the enchanted princess as she slowly opens her eyes in the sun-flooded room. A joyous fanfare sounds at the end as other storybook characters gather about her and the Good Fairy gives the happy pair her blessing. The “jardin féérique” is in the key of C Major. This deceptive and alluring melody begins in the violins, supported by a rich counterpoint of the string ensemble playing “pianissimo”.

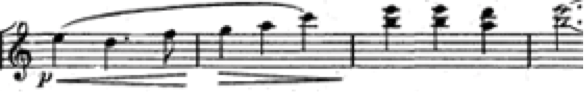

Progressively invading the orchestra, this theme is reversed, then introduces a luminous page in which the harp, the celeste and the woodwinds provide an accompaniment to the 1st violin solo.

The luminous final Coda is performed by Harp and Celesta glissandi and string tremolos in the high register imitating small bell-like sounds.

O. Respighi Trittico Botticelliano

Ottorino Respighi

Ottorino Respighi (1879 -1936)

Trittico Botticelliano (Three Botticelli Pictures) was composed after Respighi encountered three paintings: La Primavera (Spring), L’Adorazione dei Magi (The Adoration of the Magi) and La Nascita di Venere (The Birth of Venus) at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

Ottorino Respighi composed his Trittico Botticelliano in 1927. Each of the three movements of the work is based on a painting by the Italian Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli. The middle movement, L’Adorazione dei Magi, depicts Botticelli’s famous nativity scene, which interestingly uses a backdrop of the ruins of Ancient Rome, and which includes the artist’s portrait of himself at the extreme right of the painting, looking at the viewer.

I. Primavera (Spring).Spring is personified by the figure of a woman. She comes forward scattering flowers, while all Nature round about her awakes. Young women, wreathed with flowers, weave dances, the birds sing. Trills, songs, and dances follow each other in the orchestra with rhythms of joy.

The opening movement provides an exuberant depiction of spring with the bassoon first introducing a dance tune that is subsequently echoed and ornamented by the full ensemble. In addition to his work as a composer, Respighi was also a scholar of Italian music history, so it is no accident that his dance tune closely resembles one that might have accompanied the Renaissance festivities of Botticelli’s day.

2. The Adoration of the Magi. Around the hovel of Bethlehem the kings who have come from the East are in adoration. The caravans arrive with the precious gifts. Pastoral instruments play shepherds’ songs.

The second movement is really the centerpiece and is built around the ninth century Latin antiphon “Veni Emmanuel,” better known to us as the advent hymn “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel.” The mournful and mysterious opening gives way to more colorful musical textures as each of the three Magi arrive at the manger and present their gifts.

3. The Birth of Venus. From the sea, blown along by the wind, comes Venus, in a shell of mother- of-pearl. Worked through a rhythmical design which recalls the small waves of the picture, all is gentleness as the waves that bring the goddess to the shore are given sweet musical expression in the violins.

Finally, the last movement attempts to capture Botticelli’s most well known painting in which the newly born goddess Venus stands nude inside an oversized scallop shell. Respighi captures the birth through the slowly coalescing melodic materials that seem to drift from foreground to background as if carried on the waves. The piece ends with the gentle undulations of the waves slowly receding as the goddess departs.