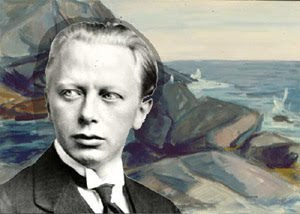

Several weeks ago, whilst browsing in the famous New York bookstore, the Strand, on the corner of 12th Street and Broadway, I came across a book on 20th Century composers and their music which included an entry for Swedish composer, Kurt Magnus Atterberg (b. 1887).

In itself, I thought this was remarkable since there is so little information about this Swedish 20th Century composer published in English, but made more so by the fact that the book was authored before Atterberg’s death on 15 February, 1974. This is the biographical entry summarised:

Though his name does not often appear in American concert programs, Kurt Atterberg is one of Sweden’s major living composers. Probably no other Swedish composer of the twentieth century has been so extensively published, performed, and admired in his own country. He belongs with those conservative men who prefer self-expression to innovation. He fills classical and well-disciplined forms with music that is romantic, though Nordic in restraint. He achieves beauty with subdued colours and tight-lipped feelings and force through understatement. Some of his best works are national in feeling, drawing their materials from Swedish folk music.

Atterberg was born in Göteborg, Sweden, on December 12, 1887, and attended the University there. Deciding to become a civil engineer (sic.) he went to Stockholm for further study. At the same time he took music lessons with Johann Andreas Hallén. From 1912 to 1914 he conducted a theater orchestra in Stockholm, holding at the same an engineering post. Subsequently, a government subsidy enabled him to abandon engineering for music, and he then turned intensively to creative work, to conducting, and to writing musical criticism.

In 1928, Atterberg was subjected to considerable criticism and publicity. At that time, his Sixth Symphony won the first prize of ten thousand dollars in a world-wide competition sponsored by the Columbia Phonograph Company. The purpose of the competition was to honour the centenary of Franz Schubert’s death with a work in the spirit of that master. Some of the critic’s, reviewing Atterberg’s symphony, pointed out numerous borrowings from the works of other composers – Rimsky-Korsakov, Elgar, Dvorak, Granados. Ernest Newman suggested that these borrowings were deliberate. Early in 1929, Atterberg wrote an article called “How I Fooled the Music World” in which he confessed that this was so, that his symphony was intended as a satire on Schubert connoisseurs, and that by winning the grand prize he had perpetrated a successful hoax.

Atterberg said that the Russians, Brahms and Reger were his musical influences. These self-acknowledged influencers are clearly evident in his Symphony No. 3 Op. 10 ‘West Coast Pictures’ (Västkustbilder) but unlike the satirical borrowings of the later prize-winning pastiche symphony, the style of writing – and especially the sophisticated orchestration (often reminiscent of latter day block-buster film scores) – is individual and the musical materials well handled.

Whereas the influence of Rimsly Korsakov is unmistakable, the acknowledgement to Brahms is less so, as thematic variation is handled entirely differently, focusing on eliding and extending rhythmic variants to the core melodic motifs as opposed to Brahms’ more expansive, contrapuntal, variation style. Of real virtue and significance is Atterberg’s handling of sonority which in may respects surpasses the oft-copied soundworld of his contemporary, Jean Sibelius. Atterberg’s soundworld is simultaneously both softer and more loud in its extremes, placing huge demands on the orchestra in respect to ensemble balance and controlling the enormity of the sonic canvas over the span of 37 or so minutes of performance time.

Son of Anders Johan Atterberg, an engineer and brother of the famous chemist Albert Atterberg, Kurt’s mother, Elvira Uddman, was the daughter of a famous male opera singer.

In 1902, Atterberg began to learn the cello, having been inspired by a concert by the Brussels String Quartet featuring a performance of Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 8. Six years later, he became a performer in the Stockholm Concert Society, now known as the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, as well as publishing his first completed work, the Rhapsody for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 1.

Although continuing to compose and conduct, Atterberg enjoyed a fulfilling career in several different organisations. He accepted a post at the Swedish Patent and Registration Office in 1912, going on to become a head of department in 1936, and working there until his retirement in 1968. He co-founded the Society of Swedish Composers in 1918, alongside other prominent composers such as Ture Rangström, Wilhelm Stenhammar and Hugo Alfvén. Six years later, he was elected president of the society, maintaining the position until 1947. At the same time, he became president of the Svenska Tonsättares Internationella Musikbyrå, which he also helped to found, and his presidency lasted until 1943. Other jobs taken on by Atterberg included his work as a music critic for the Stockholms Tidningen from 1919 to 1957, and as secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music from 1940 to 1953.

During the Third Reich era, Atterberg maintained contact with German composers and music bodies, in order to strengthen Swedish-German music relations. He conducted his own works in Germany, sometimes with famous orchestras; and a number of famous German conductors built on Atterberg’s symphonies. Atterberg never hesitated to pass the German contacts he established over the years to his Swedish colleagues, or to work for Swedish works constructed in Germany. From 1935-1938, Atterberg was General Secretary of the International Composers Council, founded by Richard Strauss in 1934.

After World War II, Atterberg wanted to free himself from suspicion of being a Nazi sympathizer. The Royal Academy of Music set up an inquiry of Atterberg at his own request. The investigation could neither confirm nor refute the accusations that he was a Nazi sympathizer.

Atterberg composed nine symphonies. His Ninth Symphony (entitled ‘Sinfonia Visionaria’) is, like Beethoven’s, scored for orchestra and chorus with vocal soloists. His output also includes six concertante works (including his Rhapsody, Op. 1, a Piano concerto and a Cello concerto), nine orchestral suites, three string quartets, five operas and two ballets.

The Symphonies form a vital part of his output. ‘Pictures of the West Coast’ (Västkustbilder) is the subtitle of the Symphony no 3 in D Op. 10 dating from 1916. It is unequivocally the best work of his symphonic output, although the Symphony No. 4 in G minor Op. 14 of 1918 (known as the ‘Piccolo’ for its brevity running to only 21 minutes) and his Symphony No. 8 are also deserved of being played far more frequently.

The Symphony No. 3 is a truly outstanding symphonic work. Highly demanding for the whole orchestra, it is in three movements:

I. Sonnenrauch (Sun Haze)

II. Sturm (Storm)

III. Sommernacht (Summer Night)

Perhaps, most extraordinarily, the work remains still in hand-written musical typeface from its publisher (making it substantively more difficult for the orchestra to read) indicative of the low demand for the work to be performed by orchestras around the world. Why this is so remains a mystery.

The work has been recorded three times, most recently by the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra under Neeme Järvi (2016). There is also an NDR recording by the NDR Radiophilharmonie from 2003 conducted by Ari Rasilainen with the earliest recording dating from 1982 by The Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of Sixten Ehrling. Each of these recordings has substantial musical errors arising from errors in the orchestral parts that have never been corrected, and so an authorative recording of the work is yet to materialize.

Atterberg married twice, first Ella Peterson, a pianist, in 1915; they divorced eight years later. His second marriage was to Margareta Dalsjö in 1925, which lasted until her death in 1962. Atterberg died on 15 February 1974 in Stockholm, aged 86, and was buried there in the Northern Cemetery.

Kevin Purcell