The music festival dedicated to the orchestral and chamber music of

The music festival dedicated to the orchestral and chamber music of

Sir Arnold Bax (1883 – 1953)

The 2019 festival features the following major orchestral works:

Tintagel

Tintagel is today perhaps the best-known – if not only orchestral work – by Sir Arnold Bax ever heard today on the concert platform. Completed in 1917; the same year as his Ballet Russes inspired stage work, From Dusk ‘Till Dawn, and inspired by Tintagel Castle situated on the Atlantic coast of Cornwall, England, the semi-programmatic work conveys, if not conjures, the dramatic legend of King Arthur’s ‘Camelot’ and the romance histories of King Mark and the illicit love between Tristran & Isolde.

From Dusk ‘Till Dawn

From Dusk ‘Till Dawn

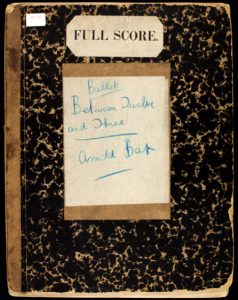

(aka ‘Between Twelve and Three’)

(Australian Premiere, in a new performing edition prepared by Troy Rogan and Play Pause Record)

This performance includes all the music from Bax’s Ballet Ruses inspired work for his ballet in one act. The ballet was produced in December 1917 with the enthusiastic balletomane, Mrs. Christopher Lowther (who also commissioned the work) – later to become Lady Cholmondley – in the lead.

Originally known as Between Twelve and Three, the story of this utterly delightful ballet is about three figurines (a figure in Dresden porcelain, a clown and a Russian ballerina) in a window sill on a Summer night who suddenly come to life at the stroke of midnight, only to return to being inanimate at sunrise.

Some of Bax’s music of this score was given in a concert performance by the young Adrian Boult on 4 March 1918, and the work was seen again on stage later that year. It then disappeared until revived in a concert at the 1982 Petworth Festival, UK. This is the first peformance since 1982, the composer’s manuscript only being rediscovered in 1981.

Courtesy of the Bax Trust and the Royal Academy of Music.

The Festival also includes a separate concert of chamber music by Bax and his contemporaries; a new documentary film on the life and music of the composer created by the ADO to further explore the remarkable accomplishments of this outstanding 20th-Century British composer.

Who was Sir Arnold Bax?

Arnold Edward Trevor Bax was born in Streatham, South London, on 8 November 1883. He studied at the Royal Academy of Music and his teachers were Frederick Corder for composition, and Tobias Matthay for piano.

While he was at the Academy Bax discovered the poetry of W. S. Yeats, and as a result visited Ireland. “I spent most of my time in the west, always seeking out the most remote places” Bax later remembered, adding “I do not think I saw the men and women passing me on the roads as real figures of flesh and blood; I looked through them back to their archetypes, and even Dublin itself seemed peopled by gods and heroic shapes from the dim past”. His love of Ireland stayed with him for the rest of his life, and for many years Irish programmes and images were reflected in his music, while he also wrote poetry, short stories and plays using the pseudonym of “Dermot O’Byrne”.

Musically Bax swayed between the influences of Irish folksong and those of Germany and, later, of Russia. However, his reputation really rests on his orchestral works, and although he wrote many of his best scores during the period 1912 to 1918, it was only after the War that they were heard and the full range of his orchestral palette appreciated. They range in scale from the exuberance of The Happy Forest (1914, orch 1921) and the delightfully evocative Summer Music (1917, orch 1921, rev 1932) to the elaboration of the Debussian Celtic tone poem The Garden of Fand (1913, orch 1916) and the grimmer landscape of November Woods (1917). Other works from this period include Nympholept (1912, orch 1915) and Spring Fire (1913), both deserving wide performance.

Musically Bax swayed between the influences of Irish folksong and those of Germany and, later, of Russia. However, his reputation really rests on his orchestral works, and although he wrote many of his best scores during the period 1912 to 1918, it was only after the War that they were heard and the full range of his orchestral palette appreciated. They range in scale from the exuberance of The Happy Forest (1914, orch 1921) and the delightfully evocative Summer Music (1917, orch 1921, rev 1932) to the elaboration of the Debussian Celtic tone poem The Garden of Fand (1913, orch 1916) and the grimmer landscape of November Woods (1917). Other works from this period include Nympholept (1912, orch 1915) and Spring Fire (1913), both deserving wide performance.

The Great War undoubtedly had an effect on Bax and his art – few could have lived through it without it leaving its mark -but Bax did not serve in the armed forces, and the event that tore his soul was undoubtedly the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916. His personal acquaintance with many of the protagonists of that “burningly idealist adventure”, his revulsion at the British reaction and his divided loyalties as well as his horror at the Irish civil war, was undoubtedly expressed in music written at the time, though by the time he came to write the powerful First Symphony (1921-2) with its tragic and elegiac slow movement his emotional reaction to human conflict was being expressed in archetypal rather than specifically personal terms.

Once launched as a symphonist Bax went on to write six more symphonies. The Second Symphony (1924-6) continues the mood expressed in the first, though now its underlying emotional thread was personal. “I was going through hell at the time” Bax remarked, and his tormented mood had to do wth his deteriorating relationship with Harriet Cohen. Later, the Third Symphony (1928-9) arrived not only at an emotional stabilisation but also signalled a conscious attempt to expand his musical language, beginning to take note of the presence of Sibelius on the musical scene of the late 1920s. It was to Sibelius that he dedicated his next work, the Winter Legends for piano and orchestra (1929-30), which together with the Fourth Symphony (1930-1) celebrated in music a new optimism in his outlook. It was at about this time that he became romantically attached to Mary Gleaves who was to remain his companion for the rest of his life, and it is persuasive to read his euphoric mood at the time in his music.

Once launched as a symphonist Bax went on to write six more symphonies. The Second Symphony (1924-6) continues the mood expressed in the first, though now its underlying emotional thread was personal. “I was going through hell at the time” Bax remarked, and his tormented mood had to do wth his deteriorating relationship with Harriet Cohen. Later, the Third Symphony (1928-9) arrived not only at an emotional stabilisation but also signalled a conscious attempt to expand his musical language, beginning to take note of the presence of Sibelius on the musical scene of the late 1920s. It was to Sibelius that he dedicated his next work, the Winter Legends for piano and orchestra (1929-30), which together with the Fourth Symphony (1930-1) celebrated in music a new optimism in his outlook. It was at about this time that he became romantically attached to Mary Gleaves who was to remain his companion for the rest of his life, and it is persuasive to read his euphoric mood at the time in his music.

During the 1930s he started receiving honours — honorary degrees, his knighthood in 1937, and in 1942 he was made Master of the King’s Music. He did not seek these, indeed he had to be persuaded into accepting, but as he became more and more celebrated, outwardly at least an establishment figure, so his will to compose gradually left him. His Fifth and Sixth Symphonies (1931-2 and 1934) revert to the emotional landscapes of the first three, while in their musical language the influence of Sibelius becomes noticeable in superficial orchestral parallels, and Tapiola is quoted in the Sixth. The Seventh and last symphony (1938-9) is a more relaxed and extrovert score and closes the door he had opened on his unique personal vision some thirty years before.

At the end of his life Bax travelled widely around Ireland, visiting all the places which he had known intimately in his youth, almost as if he was saying goodbye. He died in Cork on 3 October 1953 just short of his seventieth birthday.

At the end of his life Bax travelled widely around Ireland, visiting all the places which he had known intimately in his youth, almost as if he was saying goodbye. He died in Cork on 3 October 1953 just short of his seventieth birthday.

© Lewis Foreman [abridged]