Ivor Gurney (1890–1937)

A Gloucestershire Rhapsody (1921-22)

Ivor Gurney was born in Gloucester on 28 August 1890 and was one of four children. His father owned a small tailoring business.

He won a composition scholarship in 1911 to study at the Royal College of Music (RCM) with Charles Villiers Stanford. Of the many composers that Stanford taught, which included Vaughan Williams, Holst and Bliss, he believed Gurney to be potentially the best, yet unteachable.

It was at the RCM that Gurney met Marion Scott, who was to become a great champion of his life and work. At this time, Gurney had great enthusiasm and ideas for music in a range of genres, including a series of operas. He experimented with instrumental and chamber music but struggled with their abstract nature; song became his forte, with words providing an anchor for his musical expression. Whilst at college, Gurney lived in poverty in Fulham, and had to take a job as an organist in High Wycombe to make ends meet.

Gurney may have had a natural exuberance, but his mood would often swing to one of depression, and in 1913 he was close to a nervous breakdown which required him to take a break in Gloucestershire.

Music would have been Gurney’s career had the war not intervened. With the war in only its fourth day, he tried to enlist but was rejected due to defective eyesight. He tried again in February 1915, when the requirements had been relaxed, and this time was accepted by the 2/5th Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment as a Private, number 3895. In February 1917, the Gloucesters moved south to Ablaincourt to provide support for the French. Gurney received a bullet wound in the arm on Good Friday which was relatively minor, but he was hospitalised in Rouen for six weeks, and thus was spared most of the fighting.

Writing music while serving in France was obviously not very practical, although he is known to have written five songs while in the trenches. Instead of writing music, however, he turned more to poetry, with many of his poems evoking homesickness and a longing to return to his native Gloucestershire. Some poems recalled life in the trenches, with an acceptance of the possibility of death; others expressed his hatred of war. His first set of poems, Severn and Somme, was written in 1917, while the second, War’s Embers, appeared in 1919. As a lover of poetry, Gurney carried copies of poems with him, including poems by Keats and Housman’s A Shropshire Lad. He always had a note-book to jot down poems and ideas. After the war, he wrote songs and poetry in equal numbers, although he always regarded himself as a composer first and foremost, and believed that music was his true form of expression.

Once he had recovered from his injury, Gurney trained as a gunner with the Gloucesters, and was transferred to a machine gun battery at Passchendaele where the infamous Third Battle of Ypres was already under way. At Passchendaele around 10 September, Gurney inhaled poison gas, however, the seriousness of his injuries is unclear. It is also possible that he experienced some kind of ‘shell shock’ or trauma, as a decision was made to send him back home, where he was admitted to Bangour War Hospital in Edinburgh. Friends noted his poor physical and mental condition, but Bangour War Hospital was a progressive establishment that treated the body and mind, and encouraged culture and music. In such an environment, Gurney’s condition improved.

By November, he was discharged but he fell into depression once again. Showing increasing signs of mental instability, he returned to hospital in February 1918, and then was moved from one hospital to another, including one in Warrington for the war wounded suffering from nervous conditions. On 19 June 1918, he was found wandering by the canal in Warrington, having written suicide notes. On 4 July, with the help of Hubert Parry, he was admitted to hospital once again where he stayed until he was discharged from the army in October 1918, shortly before the armistice. With the war now over, the army took no further responsibility for his welfare; he was given a small pension, and sent out into the world to fend for himself, despite his mental condition.

After the war, Gurney returned to Gloucester with his life in disarray. His family were able to provide little support or understanding, although he did have friends who rallied round. However, he slowly recovered now he was in his familiar environment. His creative spirit returned, possibly encouraged by the publishing of his poetry, and by the autumn of 1919 he was fit enough to resume his studies at the RCM, this time being taught by Vaughan Williams. Unlike in 1911, when he first attended the RCM, he was now well known, which provided him with further encouragement. Vaughan Williams was instrumental in raising funds from friends to help him. Gurney resumed his organ post in High Wycombe, and received vital care and support from the Chapman family.

Life was now relatively stable, and musically he was at his most prolific. The years 1919 to 1921 marked a period when most of his songs were written, during a period of intense creativity.

Back in Gloucester, Gurney worked briefly as a tax clerk but was unable to sustain this due to his increasingly irregular eating and sleeping patterns. His behaviour, which was always quite eccentric, grew ever more erratic. This was hard for his family, from whom he was now virtually estranged. His family eventually sought medical help in September 1922, at which point he was certified as insane and admitted to Barnwood House Asylum in Gloucester, largely for his own safety. This was traumatic for a man who loved the outdoors and being free. He wrote letters to the police, universities, friends and colleagues seeking help in getting released, but to no avail. He did manage to escape once but was recaptured, so it was decided that he should be moved away from the familiarity of Gloucestershire.

With the help of Marion Scott, Vaughan Williams and others, he was transferred to the City of London Mental Hospital near Dartford in Kent on 21 December 1922. It was now clear he could not be cured, although he was never a threat to other people, only himself.

He may have been physically imprisoned by the asylum system, but his mind was still free, and he could live through the past. He continued to write songs (he wrote about fifty in 1925), but then he wrote nothing after 1926. His poetry remained strong though, with the past very much alive in his mind, including memories and visions of the war. In total, he possibly wrote about 900 poems, of which two thirds remain unpublished.

During the late 1930s, a group of Gurney’s friends and supporters put together a collection of articles on the composer that were to be published in Music and Letters in 1938. Drafts of the symposium were taken to Gurney for him to see, but he was too ill to understand them or recognise their significance.

Ivor Gurney died from tuberculosis on 26 December 1937, and was buried on 31 December in St Matthew’s churchyard at Twigworth near Gloucester.

Composer Gerald Finzi attended the funeral, who had come across Gurney’s music, and who, along with Marion Scott, would be responsible for gathering together his songs and poems to prepare them for publication. This was a task made difficult by the unevenness of much of his writing, and its increasing incoherence as his mental state deteriorated. Only about a hundred out of his estimated 300 songs have been published.

Of Gurney’s instrumental and chamber music, little has been published. In this genre are sonatas for violin and piano, string quartets and three orchestral pieces including, A Gloucestershire Rhapsody (see separate entry about Philip Lancaster and Ian Venables).

Much has been written about the origins of Gurney’s mental illness. Initially there was a tendency to blame it entirely on the war, and his horrific wartime experiences were no doubt part of the story, but he was already showing signs instability before he went to fight. It is now generally accepted that he had a genetic form of paranoid schizophrenia.

Ivor Gurney: A Gloucestershire Rhapsody

For A Gloucestershire Rhapsody a virtual reconstruction was required by two eminent British musciologists and composers, Ian Venables and Philip Lancaster (see biographical entries here)

Anecdotally, the ‘Rhapsody’ was long regarded as one Gurney’s most important compositions, yet in spite of this, it was not performed until 2010 at the Three Choirs Festival. This performance by the ADO is only the second live performance the work has been given, and an Australian premiere.

Philip Lancaster has described A Gloucestershire Rhapsody as “a great sweeping landscape that portrays the nobility of Gurney’s Gloucestershire.” This work does not wallow in a “clichéd rhapsodic lyricism” but cleverly presents “unity in diversity”. In parts of the score, Gurney nods towards a musical medievalism which Lancaster suggests may represent an almost Virgilian Pastoralism.

The Structure of The Rhapsody

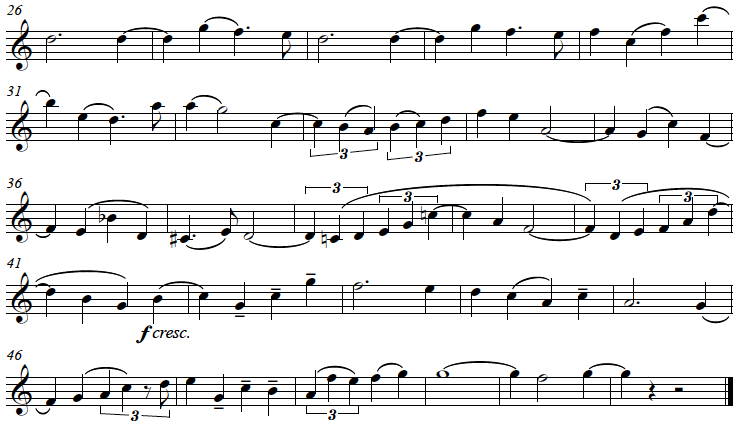

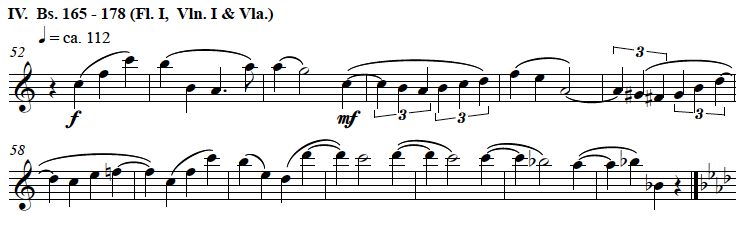

The structure of the piece, broadly speaking, is ternary in form, although it could also be construed to be in an A-B-C-b’-A’ arch-like form. One of the most striking aspects of the structure is Gurney’s use of the leading double-theme technique, where the first announcement of the melodic idea is an elided, or ‘false’ statement of a more complete working out of the melodic idea that then follows (see Example III and IV below).

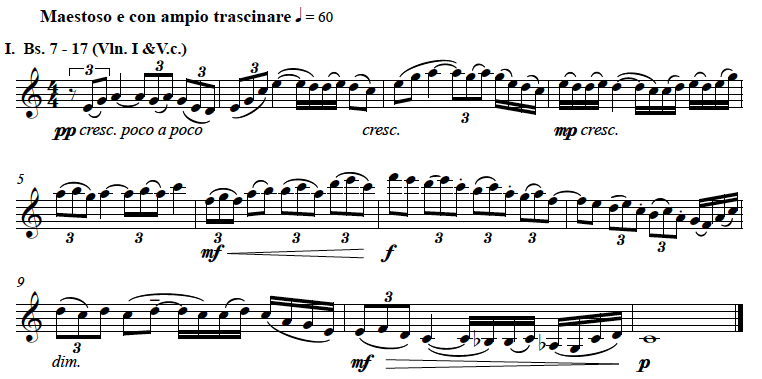

After an opening distant horn call motif – which will in extension become the major intervallic basis for the work’s major Nobilimente theme – and a short introductory, undulating passage clearly intended by the composer to represent the shape of his beloved Gloucestershire landscape (Example I)

Ex. 1.

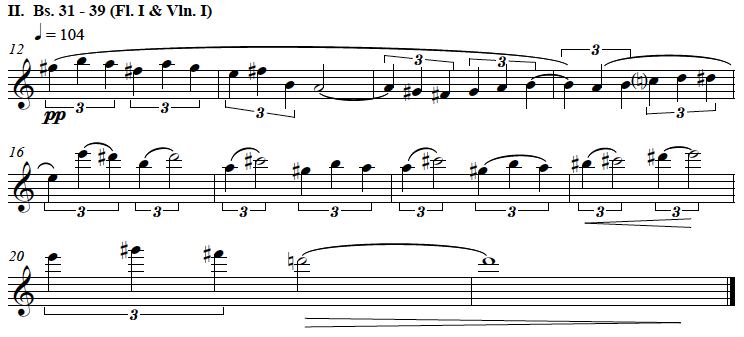

the work sets forth comprising an A section with two major long-arch themes (Example II and Examples III & IV respectively)

Ex. 2.

Ex. 3. ‘Nobilimente’

Ex. 4

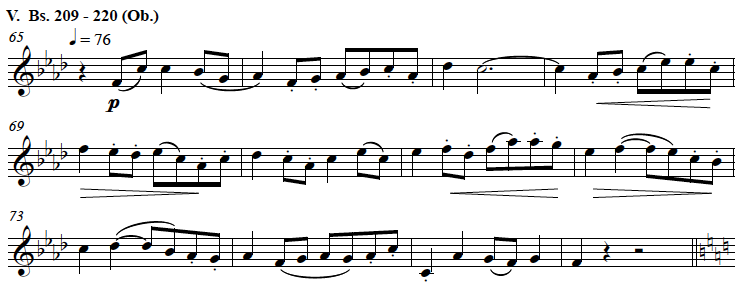

followed by a B section, built on an a slow, pastoral-like, theme for the oboe (Example V).

Ex. V

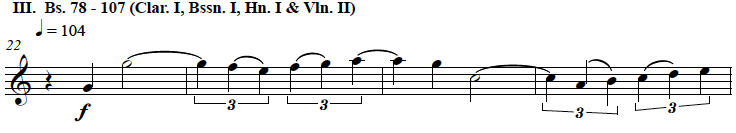

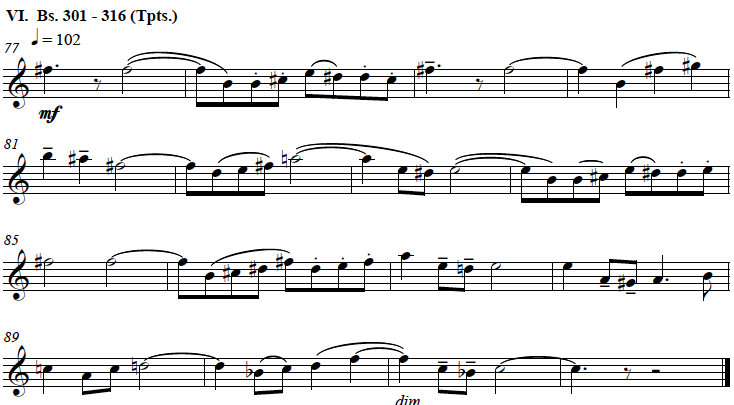

After a development-like re-working of the themes of the A section, the music turns to a fanfare-style theme for the trumpets (section C as shown in Example VI).

Ex. 6.

This fanfare is interrupted by a re-working of the undulating passage theme from the A section in a shortened re-statement, before returning to a reprise of the A section proper, the connecting material of which, interestingly, is the elaboration of a texturally more dense and harmonically altered version of the section B pastoral motif. The work concludes in a blazing largamente version of the Nobilimente theme.

Commentary

A Gloucestershire Rhapsody is a work which, according to some critics, eschews pessimism or self-pity, whilst lamenting a bygone world. It is true that the march-like themes presented in this work clearly owe much to Elgar in their ‘Nobilmente’ thematic techinque. Whereas some reviewers see Gurney’s Elgarian ‘tip-of-the-hat’ as “the onset of the high-pomps of Summer rather than reflecting the clash of empires” my personal view is that Gurney is expressing a wish for a return to an England that has been irrevocably lost as a consequence of the Great War, perhaps knowing, deep-down, that a ‘Foreign Field That is Forever England’ is an England that never existed except other than in the childhood memories of the composer’s own private ramblings through his beloved Cotswolds. In this view, Gurney’s re-working of Elgar’s Malvern Hills sound world is both apposite and highly impressive given its melodic invention.

Ultimately, A Gloucestershire Rhapsody is an indisputable masterpiece, as great as any comparable work by Vaughan Williams, Elgar or other contemporary British composers of the period.

Symphony No. 3 in B flat, Op. 104 “Westmorland” (1944)

Cecil Armstrong Gibbs (1889-1960)

Moderato (I will lift up mine eyes)

Lento (Castnel Fell)

Scherzo Vivace con fuoco (Weathers)

With complete serenity (The Lake)

Armstrong Gibbs (he always hated his first given name, Cecil) was one of the most prolific of his generation of British composers, but since his death on 12 May 1960 has become one of the most neglected. His small surviving reputation is based on a mere handful from his nearly 200 songs but he also wrote operas, incidental music, a great many choral works ranging from small unaccompanied pieces, through a long series of secular and sacred cantatas with orchestra, to the hour-long choral Symphony “Odysseus”, instrumental and chamber music including at least a dozen string quartets, and orchestral music embracing symphonic poems, concertos, numerous light music suites, and the two full-scale symphonies.

By the time Gibbs came to compose his Symphony No. 3 Westmorland, he and his family were evacuees in the Lake District – refugees, virtually, from the comfortable home now requisitioned for war purposes – with an income by no means secure, and stricken by wartime tragedy. Their son David had been killed in action on 18 November 1943, and it is impossible not to feel that this eloquent and moving work – perhaps Armstrong Gibbs’ masterpiece, and certainly his most considerable purely orchestral composition – is music both of mourning and of consolation.

The Music

The first movement (headed “I will lift up mine eyes”) begins with a 44- bar Moderato introduction which nevertheless has a numbed funereal quality, with quiet drumbeats and rolls underlying a climbing figure on horns and trombones, full of foreboding. Timpani crescendo to a decisive thump on the dominant, F, and an accelerando for the full orchestra unleashes the Allegro Deciso first subject which unfolds purposefully until it slows and cadences into D-flat major for a long (18-bar) second subject melody of great beauty and immediacy, introduced on the cellos. So memorable is it, indeed, that from here on its influence permeates the movement and indeed the remainder of the Symphony – not so much in a strictly thematic way (though it does come back literally at the end of the work), but as an emotional centre of gravity, an idealised place to be, to which the work strives to return. The melody is repeated, with richer orchestration, but its circular structure necessitates a huge effort to tear away from it and move into the development of full.

The first subject group lends itself to extension by overlapping entries, fruitful dismemberment, and redistribution amongst the orchestra; after a pause, the big tune comes back, but only its opening phrase, as a kind of feint. A passage of rushing strings seem to herald its full restatement, but instead sidesteps into a recapitulation of the first subject – but of course then the second subject, in full, pealing panoply. There is a general pause, and the music collapses back into the mood of the opening, a hushed postlude that dies away in the same muffled drumbeats.

Westmorland is a potent reaction to wartime peril, personal loss, and natural beauty, but the Lento second movement is the only one inspired by a specific place in the Lake District. After introductory exchanges on horns and woodwind, “Cartmel Fell” is evoked first by an eloquent principal subject on divided lower strings (its opening descending quavers borrowed from the first movement big tune); then a cooler, questioning second motif first heard on a solo oboe, and finally a rather Elgarian third main idea whose passionate intensity erupts like a crag through the surrounding sylvan beauty at each appearance.

Gibbs specifically labels his Vivace con fuoco third movement, “Weathers”, a scherzo, though again there is no formal ABA structure with a central trio. Bold opening timpani introduce a string of vigorous, short-lived ideas. A swinging, singing violin tune is the closest thing the movement has to a trio, but rather than leading to a restatement of the opening material (though the solo timpani does return), it keeps the lion’s share of the end of the movement to itself.

The finale, entitled “The Lake”, is another slow movement: “A day of early June, without cloud or mist. At my feet the water lies mistily blue”. For this vision Gibbs dispenses with tuba, trumpets, triangle, and cymbals throughout, and trombones apart from a few bars near the end. Oscillating thirds in clarinets frame the picture. A long main theme, unmistakably consolatory in mood, emerges on oboe; a pause, and then a solo violin picks up the melody. Another pause, and then the cellos introduce what at first seems like anew idea but is then transformed into an unmistakable reminiscence of the first movement second subject. Like a recalled chain of thought, ominousness returns with tolling timpani, and then the clouds part to reveal the finale’s main theme now on violins, the oscillating thirds transferred to violas. The first movement melody returns, darkened by trombones, and then the timpani, but at the last the solo violin soars clearly aloft into the June sky.

Though Gibbs’ superscription is unambiguous, the end of the finale is marked “Finished ad majorem Dei gloriam” Windermere November 4th 1944’. The catharsis had taken almost a year to arrive at creative fruition.

The first performance came relatively quickly, by BBC forces at Manchester on 23 August 1945, but apart from one further BBC performance, at Glasgow in 1956, the Symphony seems not to have been heard again until a live performance given by the Essex Chamber Orchestra in 2006. The performance by the Australian Discovery Orchestra in 2016 is an Australian premiere.

Extracted in part from liner notes by David J. Brown ©1994

The Life of Cecil Armstrong Gibbs

A little-known prolific English Composer, Adjudicator and Conductor, who studied under Sir Adrian Boult and Ralph Vaughan Williams, and a contemporary of Sir Arthur Bliss, Herbert Howells and Sir Arnold Bax.

Known principally for his solo songs, Armstrong Gibbs also wrote music for the stage, sacred works, three symphonies and a substantial amount of chamber music, much of which remains unpublished. He gained wide recognition during the early part of his life, but until recently, like many of his contemporaries, has been little known. He died in Chelmsford on 12th May 1960 and is buried with his wife in Danbury churchyard.

Early life

Cecil Armstrong Gibbs (he hated the name Cecil) was born in 1889 at The Vineyards, Great Baddow, Chelmsford, the first child of Ida Gibbs (née Whitehead) and David Cecil Gibbs, the famous soap and chemicals manufacturer. His mother died when he was only two years old, so he was brought up by his five maiden aunts. So apparent were his musical gifts at a young age, that the aunts begged the boy’s father to send him abroad to receive a musical education. However David Cecil, who had himself been educated in Germany, was determined to give his son the benefit of an English public school education. Consequently the young Armstrong was sent first to a preparatory school on the Hove / Brighton borders and then on to Winchester College.

Education

From Winchester, Armstrong Gibbs gained an exhibition and a sizarship to Trinity College Cambridge to read history. After completing his History Tripos in 1911 he stayed on at Cambridge to take his Mus. B. During that period he received composition and harmony lessons from E. J. Dent and Charles Wood and studied the organ briefly under Cyril Rootham. Realising that he could not make a living from composition alone, he decided to take up teaching. He spent just over a year at Copthorne School, East Grinstead, before returning to his old preparatory school, The Wick. Although he was not able to compose as much as he had hoped, he did write some songs to poems of Walter de la Mare. On being asked to produce a play for the headmaster’s retirement in 1919, Armstrong Gibbs approached de la Mare directly and was delighted when the author produced the play Crossings for him to set to music.

Entry to the Royal College of Music

The producer of the play, Armstrong Gibbs’ old composition teacher E.J. Dent, brought the young Adrian Boult down to conduct Crossings. He was so impressed with the music that he generously offered to fund Gibbs for a year as a mature student at the Royal College of Music. Encouraged by his wife, Honor, to take up the challenge, Armstrong Gibbs resigned from his post and moved back to Essex. After a year at the RCM studying conducting under Boult and composition under Vaughan Williams, he accepted a part-time teaching post at the college.

In Danbury, near Chelmsford

Soon after moving to Danbury in 1919, Armstrong Gibbs set up a choral society which then participated in the Essex Musical Association festivals in Chelmsford. The setting of one of his own compositions, for a festival class in Bath, led to his becoming an adjudicator and eventually Vice-President of the National Federation of Music Festivals. Thereafter followed a busy life of touring the country adjudicating festivals, conducting and composing. As well as conducting the Choral Society in Danbury and singing with the Church Choir, Armstrong Gibbs played cricket and bowls and lent active support to many local organisations.

The War Years

His house Crossings being requisitioned as a hospital during the Second World War, Armstrong Gibbs moved to Windermere, where he continued composing and conducting. After his son David was killed on active service in Italy he wrote his third symphony, The Westmorland. On his return to Essex in 1945 he re-formed Danbury Choral Society and renewed his association with the Festivals Movement, playing a key role in the organisation of the music for the Mothers’ Union World Wide Conference of 1948 and the Festival of Britain in 1951.

As a Man…

Armstrong Gibbs was a country man at heart who did not care to be part of the London musical scene. He played a full part in village life, serving on several committees and participating in local events. A sincere Christian, he sang in the church choir, supported the bell ringers and spent much time fund raising for the restoration of the Church Tower and Organ. He took a great interest in the local flower show and knew everyone in the village. When he grew too old to play in village cricket matches he became a keen bowls player.

Armstrong Gibbs was a warm and affectionate man, devoted to his family, and with many friends to whom he showed great loyalty and generosity. He was scrupulously fair and quick to champion anyone he felt had been unfairly treated. His great sense of humour, clearly recalled by his daughter, is borne out by the many tales he tells in his unpublished autobiography Common Time.

He had a large frame and could look imposing, particularly on formal occasions when he wore his Mus D. gown. He had a definite sense of how things should be ordered, so found it difficult to countenance other people’s opinions. He always spoke out for what he thought was right. As a young man he had red hair and a temper to match; but he was always the first to apologise after an outburst. His nervous disposition and digestive problems he put down to his father’s draconian attitudes when he was a child.

As with most people, there were contradictions in his character. For instance, the same person who could tap a young chorister on the shoulder for getting a fit of the giggles, could also himself drum on the choir stall in front of him, when the Rector was in full flood, and mutter audibly ‘Whenever will that man finish?’

The Music of Armstrong Gibbs

Although he is principally remembered as a composer of solo songs, Armstrong Gibbs was a versatile musician whose output included part songs, larger choral works, chamber music and three symphonies. Much of his chamber music remains unpublished and the few recordings that are available give scant exposure to his compositions.

Some of the well-known Gibbs settings date from the early years of his career; for example Nod, Silver, Five Eyes and A Song of Shadows, all poems by Walter de la Mare with whom he had a close artistic association. Songs from the children’s play Crossings, written by de la Mare, mark the beginning of his career as a composer.

Gibbs made his name by writing for the stage. After Crossings came the incidental music for a production of Webster’s The White Devil, in Cambridge. This was quickly followed by the music for Maeterlinck’s play The Betrothal, in 1921 and concurrently the Cambridge Greek play the Oresteia. Shortly afterwards he wrote the music for A.P, Herbert’s comic opera The Blue Peter and for Clifford Bax’s successful harlequinade Midsummer Madness. Gibbs always wanted to write a successful comic operetta and was bitterly disappointed, in the fifties, when the BBC rejected Mr Cornelius.

Much of Gibbs’ early music was written for string quartet with piano or other instruments. Often this combination was used as an accompaniment for his songs. Gibbs’ fluent writing for strings gained him the second prize in the Daily Telegraph Competition in 1934 ( String Quartet in A Major ). It also resulted in the popular Dusk – the slow waltz from his suite Fancy Dress, written for orchestra and piano. In the thirties too, he wrote Almayne, based on a 17th century air and A Spring Garland, a collection of musical pictures of flowers. A commission from the Westmorland Orchestra, in the early fifties, produced the reflective Dale and Fell suite. On the death of Walter de la Mare in 1956 Gibbs wrote the poignant Threnody for string quartet and string orchestra. Other instrumental music included pieces for violin, cello and clarinet and an oboe concerto dedicated to Leon Goossens.

What is presumed to be Gibbs first Symphony in E – an early mention referred to it as the second – was written in 1931 / 32 and performed in October 1932, under the baton of Sir Adrian Boult. The second, the choral symphony Odysseus, thought by Gibbs to be one of his best works, had to wait until 1946 for its first performance. The third symphony, the Westmorland, was completed in 1944 (following the tragic death of his son who was killed in action in Italy), while the composer and his wife were living in the Lake District.

Extracted and edited from The Armstrong Gibbs Society Website http://www.armstronggibbs.com/html/bio.htm

Please click below for a pdf version of the above commentary: